Ex Machina: Just how close to reality is Alex Garland’s robo-thriller?

Alex Garland’s directorial debut imagines a world with artificial intelligence as advanced as our brains. But how far away is it, and will it spell the end for humanity?

With Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk recently warning the world of the dangers of artificial intelligence, 28 Days Later writer Alex Garland couldn’t have picked a better time to release his directorial debut.

Ex Machina tells the story of a 24-year-old coder called Caleb who wins a competition to act as the human component in a Turing Test run by his billionaire boss Nathan – played by Oscar Isaac as a cross between Mark Zuckerberg and a Bond villain. One minute he’s sweating out a hangover in his home gym and dancing with his live-in maid like a #LAD Steve Jobs, the next he’s intimidating Caleb from the shadows of his concrete-walled lair deep in the wilderness.

Ava little thing she does is magic

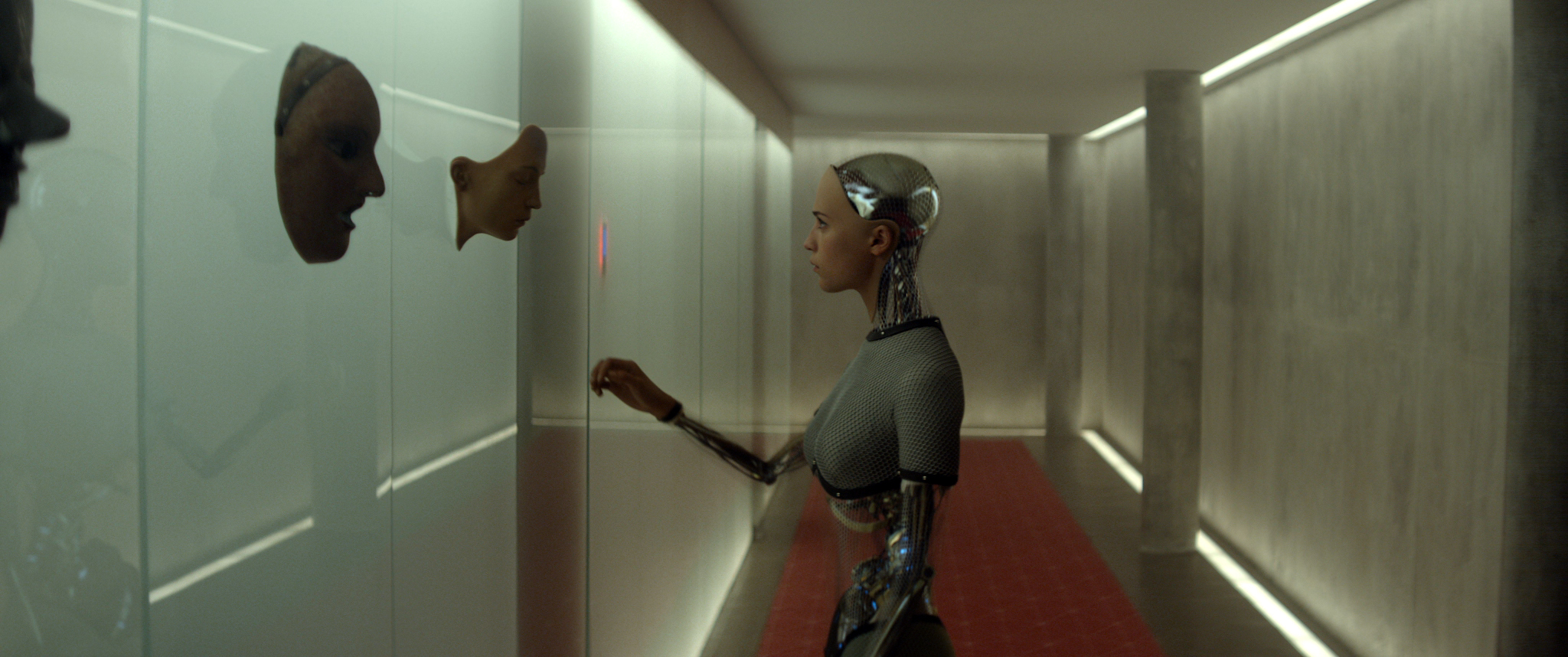

Nathan’s latest invention is Ava – a walking, talking robot with artificial intelligence that he hopes is indistinguishable from that of a human, even when the tester can see she’s an android with his very own eyes.

“I want people to forget that Ava is a robot, while seeing that she’s a robot,” Garland tells Stuff when we meet in London.

“Humans find it really easy to project emotion onto inanimate objects, let alone animate objects. It’s very easy to find a child that believes their teddy bear has sentience; the tricky thing would be finding one that says it’s just a bit of old cloth and some stuffing.”

And it works. Ava is so convincing as a human largely due to the way she’s depicted on screen. While Andy Serkis has done incredible things creating fully computer-generated characters within live-action films, such as primate-in-chief Caesar in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, Ava is a real blend of practical and visual effects.

Garland explains how actress Alicia Vikander wore a prosthetic that created a kind of mask face so there’s something to map the CGI on to, plus a bodysuit, which is the mesh you see over her chest and shoulders.

“If you actually made Ava in the way that she’s constructed she’d probably just fall over,” he admits, but in the film the effect is one of the most convincing combinations of CGI and live action Stuff has ever seen.

Dr Robotics

In an attempt to strike a balance between pure sci-fi and a believable, present-day reality, Garland employed the expertise offered by Murray Shanahan, a professor of cognitive robotics at Imperial College London, and Adam Rutherford, a scientist, writer and broadcaster. So how far from Ava is Honda’s famed Asimo ‘bot?

“In many ways Asimo’s pretty primitive,” says Shanahan, probably recalling that video of Honda’s pride and joy tumbling down a set of stairs. “If you’ve ever seen Boston Dynamics’ Big Dog, that’s a much more realistic way of walking. Asimo calculates every single step, which is very biologically unrealistic.”

But Ava isn’t. She can dress herself, draw and move pretty much like a human being. She’s a triumph of soft robotics, albeit one that’s not possible just yet. “When it comes to the hardware it’s a matter of engineering,” Shanahan says. “Most robotics these days is made using very hard materials, whereas the stuff we’re made of is soft, pliable and compliant. But eventually we are going to be able to produce humanoid robots that are really very sophisticated and Ava-like.”

“Don’t forget we have a four-billion-year advantage over designing robots because we’ve evolved to be like this,” adds Rutherford. “We are such fluid machines and our mechanics are really sophisticated. I did some stuff with a company based in San Francisco that can get robots to drive cars, walk and jump, but they cannot make them get into cars. I thought that was really striking because it says something about the complexity of physicality.”

READ MORE: The 30 best things on Netflix right now

Knowledge is power

But what about the stuff inside Ava’s head? The development of hardware and AI isn’t necessarily linked, so just because Asimo handles stairs like a drunk, doesn’t mean he and his robo-buddies must have the mental capacity of one too, right?

“We’re in need of a few conceptual breakthroughs before we get anything that resembles human-level artificial intelligence,” reveals Shanahan, “and I can’t see that happening in the next 10 years. I think it probably will happen in the next 100 years.”

In that case we’ve got plenty of time to work out how these AIs will work, and in Ex Machina Nathan uses methods to teach Ava about the world that Shanahan and Rutherford see as being perfectly viable. After all, there are plenty of mundane examples of AI in action in our everyday lives already: Google’s search predictions, targeted online adverts and Twitter bots. Sure, they’re not likely to power an android’s brain anytime soon but using the internet to inform an AI isn’t pure science-fiction.

“There’s a truly enormous repository of data out there about human behaviour,” explains Shanahan. “Not just textual but videos and pictures, and a sophisticated machine learning algorithm can learn a huge amount from that.”

The spy who tweets me

Of course, there are also negative implications to that sort of data farming and they’re not lost on Garland. “I’m not on Twitter and I’ve never been on Facebook or MySpace or anything like that. It has never occurred to me that I would want to tweet something,” he says.

“I do feel concerned about it though. I think we were correctly worried about Snowden and the NSA, and what he did was brilliant. But ultimately in that instance we were talking about governments, and governments are elected. As citizens, although we may or may not exercise the power, we do have the power to vote them out and that’s important.

“You don’t have that power with private corporations, you really don’t. It’s disingenuous to say you’ve got a capitalist power as a consumer to choose to not buy those things, because if they’re all doing it, that means not having a phone, not having a credit card, not having a computer, not having a television and it goes on.”

Law and order

Obviously that’s just one of many issues surrounding artificial intelligence and how its development might affect us as humans. Robots have been breaking Isaac Asimov’s Laws of Robotics in films for years, but do they even stand up more than 80 years after they were first published? Or are there new rules that real-life robotics experts follow in hope of keeping us safe from our potential new overlords?

“The thing about those laws is that you’re presupposing that you’ve got something capable of actually interpreting them and reasoning through the ambiguity of them. We’re not at the point that they’re even relevant yet,” Shanahan explains.

Rutherford compares them with the Ten Commandments. While plenty of people follow them to the letter there are plenty of others who use them as a guideline. “We use various religious and philosophical models as frameworks for behaviour because life is complex,” he says before adding: “Don’t destroy humanity is, I think, a basic premise in all science.”

The imitation blame

Stephen Hawking recently suggested that artificial intelligence could be the cause of a real-life Judgement Day for the human race. Do Ex Machina‘s experts agree? “The one thing the media hates is a balanced message,” Shanahan says. “If things go a particular way things could be bad and we have to be careful to avoid that, but there’s a lot of sophisticated thinking behind those views that Stephen Hawking expressed. When it gets encapsulated in a 20-second soundbite all of the intellectual nuance underneath it is lost.”

Garland agrees: “If we’re talking about AI as a conscious self-aware machine with an emotional life in the same way we have one, what you’re saying is that the creation of a new consciousness is something innately problematic.

"I would say that every time people have a child they create a new consciousness, so I don’t feel necessarily alarmed by it. I also think that it’s perfectly possible that the new consciousness might be better than us in various sorts of ways – if that’s the case why on earth would I want to stop it?”

READ MORE: The movies to be excited about in 2015