The weekend read: How Canabalt jumped from indie game jam to the Museum of Modern Art

First Adam Saltsman’s tiny running man kickstarted a one-thumb gaming revolution - now it's rubbing shoulders with gaming legends in New York

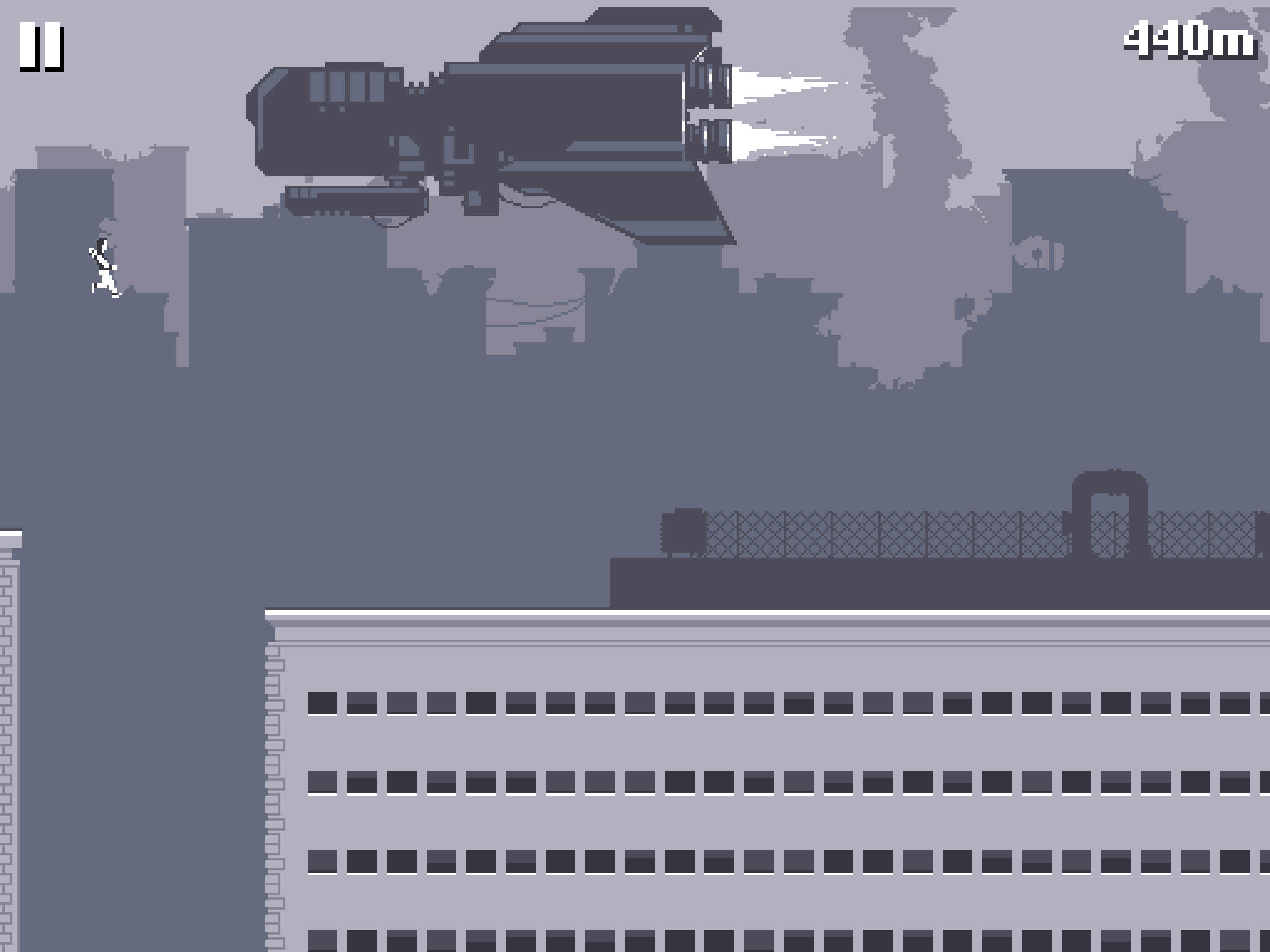

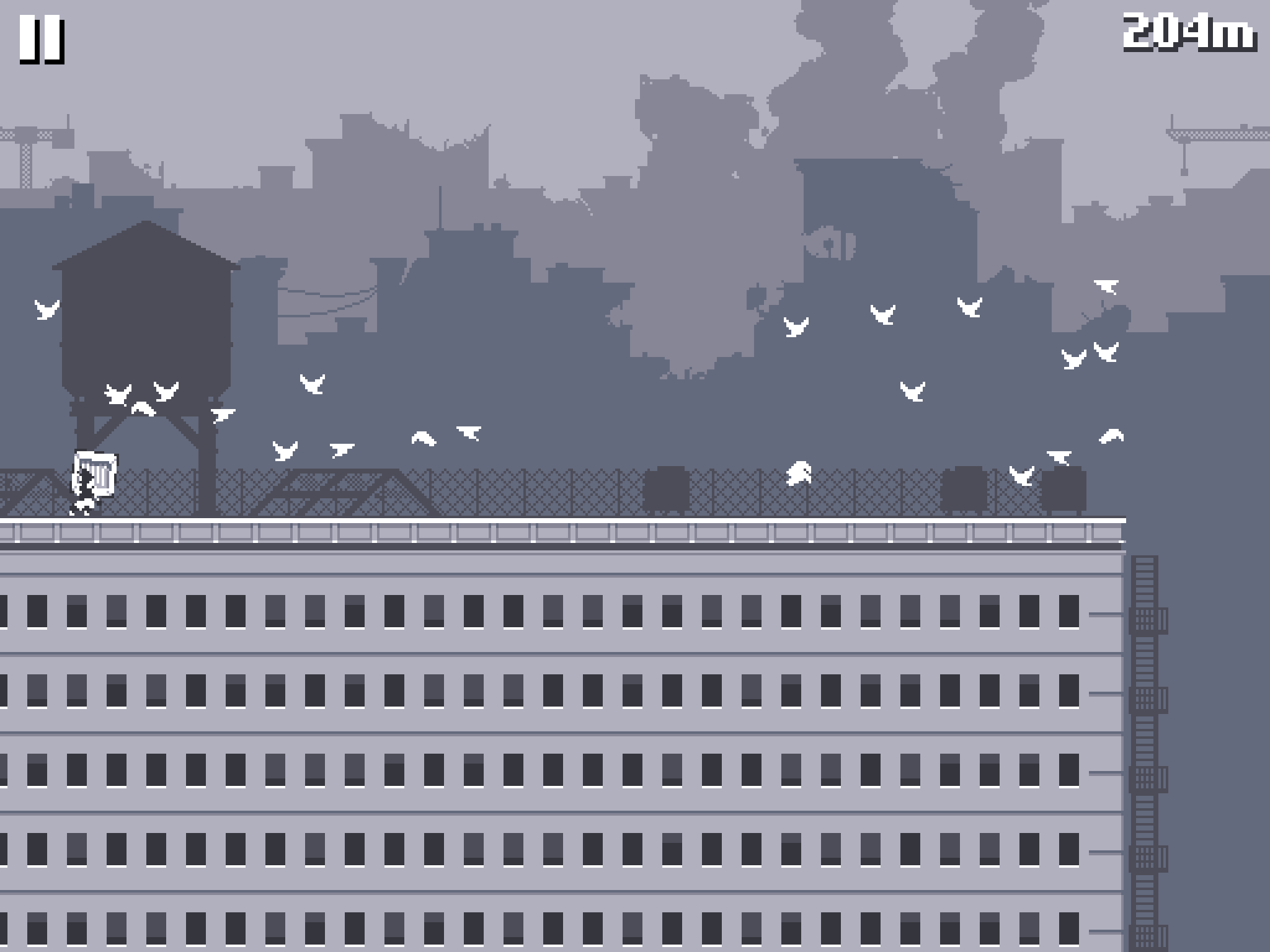

You charge along an office corridor. Seconds later, you jump through a glass window, revealing an enormous apocalypse. A massive jet flies by in a cloud of smoke as your frantic rooftop escape spooks a flock of doves.

You don’t need to learn any controls — just click or tap to time jumps as you head towards breakneck pace. This is Canabalt, a web, mobile — and now Steam — one-button classic that leapt from game jam to the Museum of Modern Art.

Origin story

Canabalt creator Adam Saltsman says his game’s origins go back to the Experimental Gameplay Project, which started life at Carnegie Mellon University: “I’d not heard of anything like it before — the idea of creating a very small game every week, for months on end.”

He recalls most EGP games were awful, and everything was done in Flash, but it was “fast, loose and flexible”. Most of all, “it was inspiring”.

The Experimental Gameplay Project rebooted into a similar internet-wide concern, and Adam became involved. An early theme was minimalism. “I’d worked as a freelance artist for pre-iPhone mobile games. Those phones were unbelievably bad! The buttons were terrible, and you often couldn’t press two at once.”

Adam became fascinated by skill-based one-button effort Tower Bloxx, which had worked around control limitations: you simply pressed a button to make a block fall on to a tottering stack.

Around the same time, he was watching Super Mario Bros. speed-runs, where optimal routes were so nailed down it was like viewing tool-assisted runs of more complex games, where the player never stops moving forwards. “They were just hitting the jump button at the right time, and for the right duration. I thought: you could make a game out of this!”

Testing

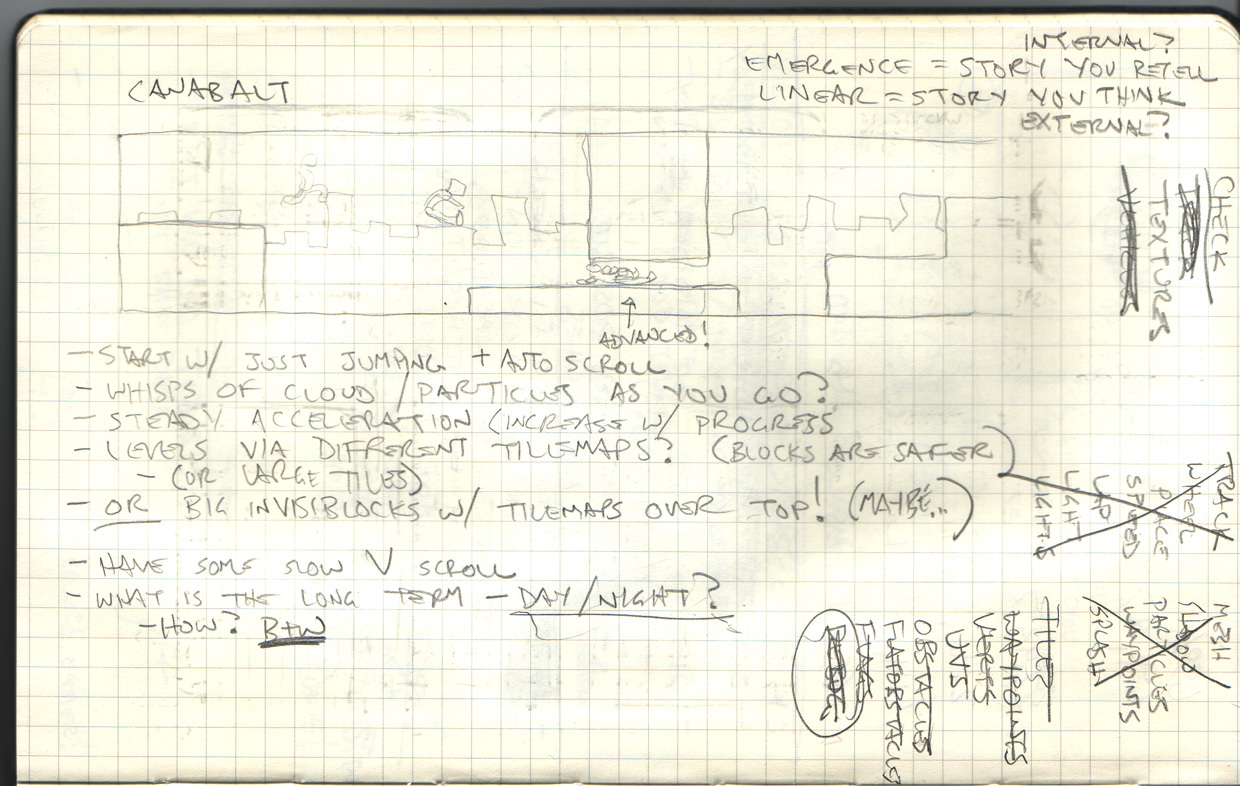

The first version of Canabalt was made in a few days, in part at an Arizona game jam; the name arrived from Adam’s then six-year-old nephew’s trouble in pronouncing ‘catapult’. Almost immediately, the game design fell out naturally. “As soon as I thought ‘Super Mario with one button’, obstacles and level structures became obvious.”

The initial build was basic: green rectangles loomed on a black background; large shapes to run on and small gaps to jump over ensured the gameplay felt good as you leapt between the green ‘buildings’ and through windows. Canabalt then went a bit apocalyptic.

“At the time, indie games were taking off, and although a lot of them had neat gameplay, the backgrounds would often be empty, or just a gradient,” says Adam. “There was no sense of place or atmosphere. I figured it couldn’t hurt to have something there — *why* were you jumping over rooftops?”

A lengthy intro was ditched, because it would take too long to make; Adam instead decided to create a “super cool” background, since he could “do that in about ten minutes”. Naturally, it took far longer, once the ‘destroyed city’ background added robots kicking each-other to death, their actions driven by bespoke AI routines.

“But this gave you that sense of place, and I added nods to games I liked, such as the alien fighter-jet fly-by in the first level of Quake II,” says Adam. “It’s a really small thing that makes the world feel really big. So there are jet fly-bys in Canabalt, and you end up viewing this really big apocalypse through a keyhole.”

Fast and furious

Two further elements completed the basics of the game: randomness and speed. As someone who dislikes memorisation games, Adam decided Canabalt would be more about building a skill set, hence the ongoing challenge being procedurally generated. “Level editing would have been a nightmare anyway,” he adds. “And so Canabalt‘s landscape is reworked on the fly, reacting to the player. If you hit a crate and slow down, you should still be able to make the next jump — unless you’ve hit too many and are barely moving!”

As for speed, Adam’s sense was most one-button games just weren’t that exciting, and he aimed to buck the trend. “Canabalt‘s one of those games where what you have to do is very easy, but you have to do it loads of times. It becomes this zen kind of thing,” he says. “It requires this really weird form of self-control, and you end up in this exciting but super chill-out flow state as the game gets fast. It’s a really weird thing that fell out of the design that I’m very happy happened.”

Launch day

Canabalt‘s 2009 debut was online, as a browser game. Adam recalls it immediately “went bananas”, chewing through bandwidth. He puts the game’s viral nature down to simplicity, the randomly generated ongoing challenge, and ultra-wide cinematic staging: “You didn’t have to learn anything, it looked kind of cool, and when you jumped out of that window, you’d already seen those first few seconds, but everything else was a kind of different challenge, every time”.

Success online drove an inevitable iPhone port. Adam figured if one-button games could work on a “crappy candy-bar phone”, they should be fine on a touchscreen, especially since so many developers at the time were struggling with terrible virtual joypads.

A Twitter campaign to purchase the game on release day propelled Canabalt into the App Store charts, keeping it visible and self-sustaining for a while. Soon, a sub-genre emerged, with titles riffing off of Canabalt.

“The game has still sold maybe only a few hundred thousand copies on iPhone, but it was always very popular with game designers, maybe because it presents itself as a template,” thinks Adam. “Part of the reason it was so stripped down was because I wanted to concentrate on something really important to me: go fast! And to get maximum speed, you have to gut everything else. But slow the game down, and you can add kicks and coins and guns and whatever. Which is all good, because I didn’t care about any of that stuff myself.”

Related › Game of Thrones: A Telltale Game review

Jump!

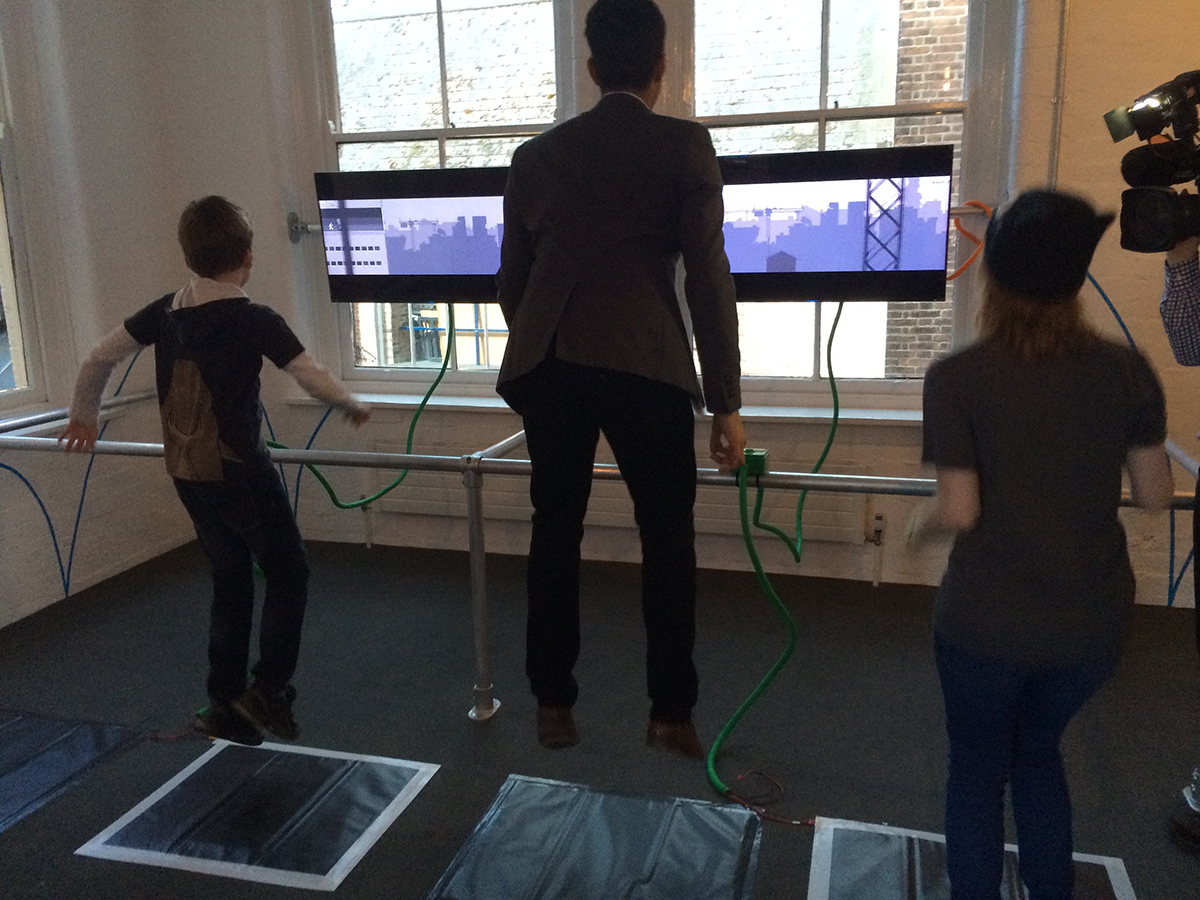

Most recently, Adam’s tiny, tightly focused game made two cultural leaps, becoming part of the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent videogame collection, and featuring in the launch exhibition at the UK’s National Video Game Arcade.

Adam had been involved with GameCity, the organisation behind the National Video Game Arcade, for some time, running events and sharing ideas. Canabalt had existed there in a couple of formats, and was deemed a perfect fit for launch exhibition ‘Jump!’.

The end result rigged up physical mats for players to jump off of, triggering the equivalent on-screen action. “I’ve a soft spot for taking games into the physical,” says Adam, remembering another event that dressed players in a boiler suit, then immersed them in a contraption housed in a freezing basement, for a “terrifying physical experience”.

Canabalt‘s reworked version wasn’t nearly so cruel, bar its sudden difficulty spike: as players discovered, physical Canabalt is insanely hard. “It becomes enormously challenging, but doesn’t seem like it should be,” thinks Adam. “You rationally understand the gap between the real-world and a videogame, think you’ll hop and be fine — but the worlds are so different, which I really like.”

Where are they now?

As for Canabalt and MOMA, Adam says that experience was “weird and awesome”. Canabalt became part of a small hand-picked collection, which included Tetris, The Sims, Pac-Man and Myst, and Adam says it meant a lot to have his work placed next to titles he’s looked up to and been inspired by. However, he notes that games are part of the museum’s design collection. So rather than rubbing shoulders with the likes of a Dali or Duchamp, they’re considered bedfellows to “weird chairs and the iPod”.

While there’s a sense games are finally being considered culturally valid, Adam considers it strange they’re now part of an archive primarily about things that are utilitarian in some way, or whose identifying signature element is usability.

“Games are really mostly about wasting time — about unnecessary obstacles and things getting in your way. They’re about going the long way round, because that’s what’s interesting,” he says, adding that games have more differences than similarities to industrial design.

Stuff proffers that it’s good that institutions such as MOMA are finally understanding the relevance of games, even if they’re a bit confused about where to place them.

“Yeah, and I kinda feel that the longer people are confused about games and what to do with them, the better,” adds Adam. “That’s a happy, good place, to be, because it means it’s still OK to do pretty big experiments.” Experiments like Canabalt.

*Canabalt is available on iOS, Google Play, Steam and online. All versions can be found via canabalt.com. Adam Saltsman is on Twitter

Related › The top 10 games in the world right now