Why Apple’s ResearchKit is more exciting than a new MacBook or Apple Watch

An Apple a day may prove good for your health, through turning an iPhone into a cutting-edge diagnostic tool

An irritating aspect of tech companies is banging on about how their devices will change the world; and at any given Apple event, the company’s execs make such a claim approximately every eleven seconds.

But on 9 March 2015, sandwiched between HBO Now and new MacBook reveals, and well before the Apple Watch loomed into view, was an announcement that bettered any shiny trinket and could genuinely transform people’s lives: ResearchKit.

This new framework builds on the health hub Apple created with HealthKit, but extends it into the world of medical research. Apple’s Jeff Williams briefly quipped that medical research was not what the audience was expecting from the day’s event. Too right: they were waiting to find out how much a new Apple Watch would cost. Undeterred, Williams went on to outline huge challenges facing researchers in the industry.

Recruiting people for studies is tricky, often requiring payment, and even then input can be limited. Kathryn Schmitz, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania, noted in a video how of 60,000 letters sent out, only a paltry 305 responses were received. With small sample sizes, researchers do not get a good cross-section of the population, which in turn limits their understanding of disease.

Furthermore, data collection is often subjective; for example, Parkinson’s disease assessment may involve a patient walking in front of a physician and being ‘rated’ on a scale of zero to four. Other complications in research include infrequent data collection that doesn’t capture the ebb and flow of disease, and one-way communication, with people participating in studies but never hearing anything in return. In short, the process can be sporadic and dispiriting, alienating the very people it’s trying to help.

With 700 million iPhones in the wild, Apple figured out a way to make its device more than a slab of metal for gorging on Facebook and checking emails 500 times before lunch, nudging medical data collection out of the rut it’s apparently been stuck in for decades.

Williams proudly noted how ResearchKit and an iPhone could combine to become a powerful diagnostic tool, and briefly covered five apps built alongside well-known institutions, all aiming to target serious diseases.

Asthma Health is the most audacious, through a ‘phase two’ planned for New York City. There, Mount Sinai Hospital will give away spirometers and Bluetooth inhalers, and swab city surfaces to look for pathogens. iPhone GPS coordinates will be cross-referenced with data collected from other devices, in an attempt to tie exacerbation to the pathogen map, thereby discovering triggers.

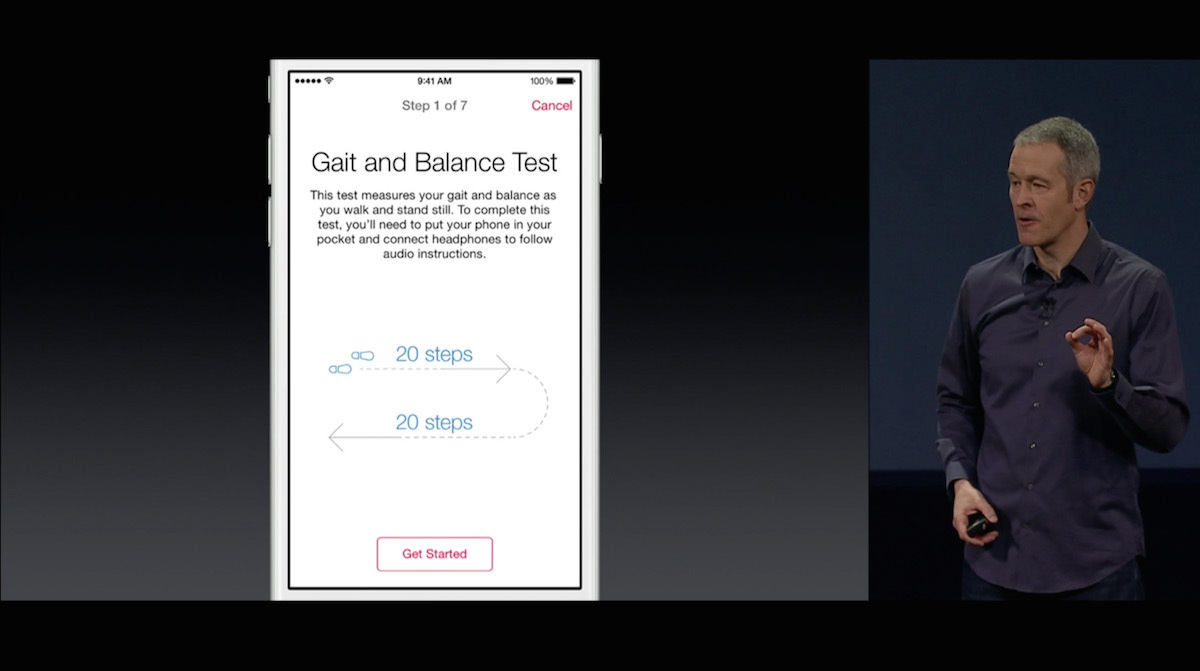

But even for more typical use cases, ResearchKit could change how medical research is carried out. With Parkinson’s, for example, the mPower app includes tapping tests that evaluate hand tremors, a speech test for detecting vocal cord variations, and a walking test that leverages the iPhone’s accelerometer and gyroscope, to measure gait and balance. All these tests can be done wherever you like, rather than in a doctor’s office.

Additionally, apps can pull in other data from HealthKit, giving the user an ongoing overview of their health and condition. They can then more easily map behaviour to how they feel at any given time. So while optionally providing data to a broader study attempting to discover global patterns and move research onwards, a sole user may come to understand how certain exercise affects their own well-being.

Apple’s system, then, cleverly puts people at the centre of medical research while potentially hugely increasing the scale of the amount of collected data, including access to people who’ve never been willing or able to participate in studies.

Williams added that data would be secure and unavailable to Apple, and that anyone should be able to contribute, regardless of the platform they’re using. Apple’s therefore making ResearchKit open source, thereby saving Samsung from having to warm up its photocopier.

The size of a screen or thinness of a device; switchable parts or a better camera. These are all ultimately bullet-points in a spec list – transient bragging fodder that will be forgotten about tomorrow. But when Schmitz enthuses that she could “kick out a survey to patients every day […] that would show up on their phone and actually improve their health and our ability to care for them… that is a game-changer,” she does so without hyperbole.

Apple often says it wants to change the world. With ResearchKit, for a great many people, it now might – and in the most important way of all: quality of life.