Pay for music, films and games, or you’ll be left with garbage

Home taping never killed creative industries, says Craig Grannell, but the current race-to-the-bottom is having a damn good go

I grew up during the first great era of piracy.

Pretty much everywhere you turned, you’d see someone telling you that if you were naughty and copied anything, entire industries would crumble, and policemen would whisk you away to enjoy a life of breaking rocks with a hammer while burly convicts broke your face.

Of course, that didn’t happen.

We copied terrible music on to creaky cassettes and swapped them with friends, and ‘backed-up’ 8-bit videogames that somehow also found their way to the playground.

As technology evolved, so too did the copies, tapes giving way to CDRs. To my knowledge, precisely no-one I knew got arrested. I suspect the police had better things to do than set up an elaborate sting operation to thwart a nine-year-old’s plans to trade a dodgy copy of Monty On The Run for half a Marathon bar.

At some point, though, copies became the exception rather than the rule. This was probably when we started earning money.

Sure, we’d still happily trade the odd game or CD for a while, but we’d also spend substantial sums of cash on new records, videos, books, comics and games.

Home taping hadn’t killed the music industry, video games or television: it had merely fuelled our interest in them, broadened our horizons, and set things up nicely for that point where disposable income introduced itself with a toothy grin.

Looking around today, this line of thinking – actually paying for media – is becoming increasingly alien. For many people, there’s a level of entitlement that’s truly staggering: the assumption that everything in the world of entertainment should be dirt-cheap or free.

People whine about amazing 69p mobile games ‘only’ lasting a few hours, or breakthrough TV shows being priced at 15 quid for a season’s worth on a DVD.

This has all been fuelled by the race-to-the-bottom across various online stores and streaming services, possibly torpedoing for good the concept of value within this space.

Couple that with a generation of teens that’s never known anything other than the internet, torrenting, and getting everything for free, and you have a recipe for change to the media landscape. In the sense that setting fire to all your clothes is a change to your wardrobe.

This could all be viewed as a very good thing, in that people today have almost instant access to a huge range of content – an astonishing amount of past and present novels, films, games and more. Plus, you might argue that technology also affords those doing the creating access to a larger audience than ever.

But with people increasingly delving into digital and yet becoming less likely to pay, those making content may soon be devoid of income from it. You might argue that no-one owes anyone a living, least of all people faffing about all day writing or making music, and that’s fair enough.

And yet our culture is so heavily indebted to great media that the prospect that we might one day have to do without it is truly terrifying.

It’s hard to see what’s in store in a decade’s time. Perhaps more creative types will become hobbyists, but that eradicates any kind of schedule and hampers the scope of what might be achieved.

Maybe we’ll increasingly see the return of a more overt class-oriented art and culture split, where those who can afford a creative lifestyle get the opportunity to play at being pop star or author, whereas everyone else cannot.

Worse, there’s the very real likelihood media will reduced to lowest-common-denominator content with extremely mass-market appeal that draws in enough eyeballs to appease advertisers. Everything will be financed by brands, nothing will take risks or cause offence, and creativity and objectivity will be wrecked. Sounds amazing.

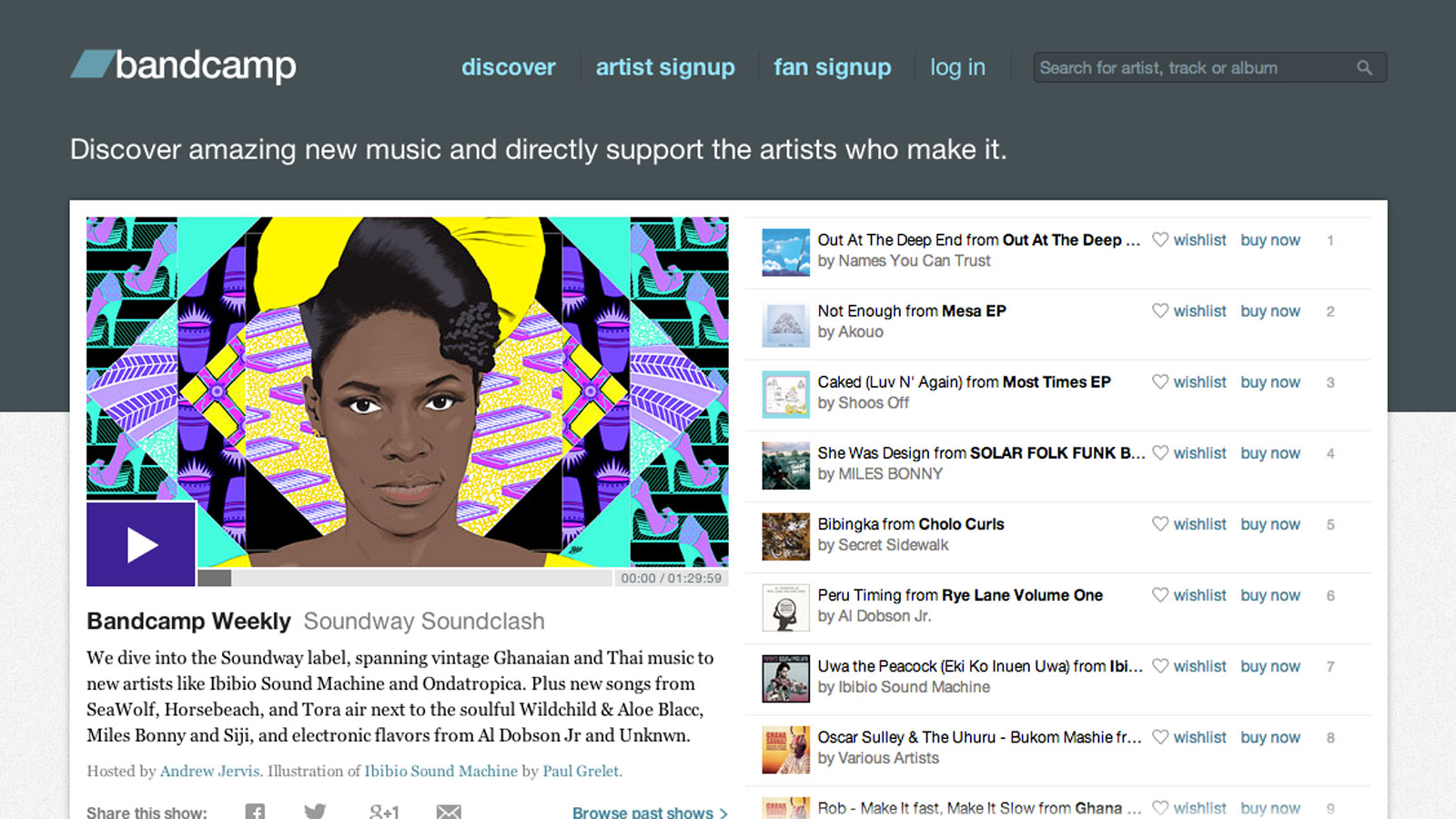

There are beacons of hope: original series on Netflix; Bandcamp enabling musicians to easily market and sell music online; the slow but steady rise of commercial digital comics; fans of great content recognising what’s happening and making an effort to spend rather than download.

But it feels like screaming into the wind, and every time someone opens their BitTorrent client rather than their wallet, we inch closer to that point where Dancing Brother Idol Factor On Ice (directed by Michael Bay) sits atop every chart for the rest of our lives.

READ MORE: These are the 100 best gadgets ever