Why you should be pumped about (and just a bit sceptical of) Hi-Res Audio

UPDATED 17/06/14: Record labels agree on standardised definition and categories for hi-res audio

On the surface, things aren’t looking particularly rosy for lovers of high quality music formats.

For teenagers, YouTube has become the go-to method for listening to songs, while most other people, even die-hard music addicts, eschew spending big on physical formats in favour of cheap and convenient compressed digital alternatives like MP3 downloads and Spotify streaming. It’s enough to make an audiophile weep into his teetering stack of 180gm Pink Floyd re-issues.

But these trends don’t tell the whole story. Hi-Res Audio might just explode in the coming year, with manufacturers and musicians alike hopping aboard the audiophile express. Or, it might not. Read on to find out why Hi-Res Audio is so interesting, and why it might also remain a very niche concern.

So what is hi-res audio? Hi-def TV for my ears?

Good question – and one for which there are several possible answers. Unlike HDTV, there isn’t a set standard for what constitutes Hi-Res Audio, but generally it’s considered to be anything with a bit depth and sampling frequency above 16-bit/44.1kHz, which is standard CD quality. 24-bit/192kHz is considered the Holy Grail of Hi-Res Audio, but ‘lesser’ qualities like 24-bit/96kHz are still hi-res.

The more bits, the more accurately the signal is measured. The higher the sampling frequency, the more samples-per-second were taken when the original analogue sound was converted into digital.

Confusingly, Hi-Res Audio can come in a variety of file formats. There’s FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec), ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec), WAV, AIFF and DSD. The first two are compressed formats, which might suggest they’re inferior to the others – but they’re also lossless, which means they’re compressed in such a way that no audio data is lost. So they take up less disk space than the others but sound exactly the same.

Note, however, that not every file in one of the above formats is hi-res. Plenty of people use FLAC or ALAC to rip CDs losslessly, for instance – in which case the file played back is CD quality, not hi-res.

Update 17/06/14: Record labels and consumer electronics groups have got together to lock down the definition of what, exactly, hi-res audio is. The Digital Entertainment Group, the Consumer Electronics Association and The Recording Academy have teamed up with Sony, Universal and Warner Music Group to come up with a standard definition for high resolution audio: "Lossless audio that is capable of reproducing the full range of sound from recordings that have been mastered from better than CD-quality music sources."

Four different file formats have also been agreed: MQ-P; MQ-A; MQ-C; and MQ-D. "MQ" stands for "Master Quality", meaning that the file is produced from a digital or analogue master recording. The file types are as follows:

Although the Master Quality file types and definition of hi-res audio are voluntary, the hope is that with major players backing them, they’ll come to be a de facto standard.

And why now?

There have been attempts to popularise Hi-Res Audio in the past, most notably with the DVD-Audio and SACD disc formats, both of which entered the market in 2000 to what might be generously described as “limited success”. That didn’t work out – so why is now any different?

Firstly, there’s a concerted push from a loose partnership consisting of the Consumer Electronics Association (the organisation behind CES Las Vegas), Sony Electronics, and the three major music publishers (Sony, Warner and Universal). The CEA’s job is to market the idea (much like it has done in recent years with HDTV, 3D TV and 4K), Sony’s is to build compatible hardware and the record companies’ is to make hi-res music more readily available.

And we’ve recently seen the very first hi-res compatible smartphones released in the forms of the LG G2 and Samsung Galaxy Note 3 (both capable of playing FLAC and WAV at 24-bit/192kHz quality), and there’ll be more launched next year.

Rock legend Neil Young is also releasing his Pono portable music player – and an accompanying library of studio master quality albums – in “early 2014”. Details on Pono are fairly scant, but it will be 24-bit/192kHz compatible and albums released for the first time in hi-res through the store will include the likes of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited.

Making hi-res available for listening via smartphone or portable device (such as the Sony NWZ-F886 detailed below) is extremely important, as most non-audiophiles don’t sit at home listening to music through incredibly expensive hi-fi equipment – they listen through their phones when they’re out and about. You want to capture the younger market? You need to put hi-res on portable devices.

Storage is also cheaper than ever, meaning it’s somewhat less of a headache accommodating the huge files required for Hi-Res Audio. 24-bit/96kHz files weigh in at 34.56MB per minute, compared to 1.44MB per minute for 192kbps MP3s. That’s 24 times the space.

So what do I need to listen to it?

There are plenty of hi-fi products compatible with Hi-Res Audio, from streamers like the Cambridge Audio Minx Xi and Pioneer N-50 to networked AV receivers like the Marantz NR1504. While some of these come in at the affordable end of the spectrum, once you add speakers, cables and network storage to the mix you’re looking at a big spend.

As we mentioned above, Sony has gone on a real Hi-Res Audio push of late. You can read about the products the company has launched in more depth here, but suffice to say: if you’re looking for an easy (dare we say idiot-proof) way to get into hi-res music, Sony is the company offering the closest thing. Its HAP-S1 micro system, for instance, is a one-box solution with built-in amplifier, 500GB of expandable storage, Wi-Fi, DLNA, touchscreen controls and compatibility with all the major hi-res formats, all for £800. Add a pair of speakers and you’re ready.

Even simpler is the NWZ-F886 (£240), Sony’s Android-based Walkman digital music player. It supports 24-bit/192kHz and carries a built-in digital amp – although its 32GB of storage will fill up quickly if you do opt for those hi-res files.

You can also listen to 24-bit files on your computer, via software like Winamp or VLC (iTunes does not yet support 24-bit). Unless your PC or Mac has a top class sound card, a DAC or headphone amp makes a welcome investment in this case. You can check out some of our favourite DACs here.

And where do I get it?

This is a key point, because if there’s barely any hi-res music to listen to, it will never become more than a niche market. That’s the fate that befell SACD and DVD-Audio when it became clear to listeners that the labels weren’t really taking either format seriously, releasing mostly old remastered albums alongside the odd new album and the audiophile (but very niche) staples of jazz and classical records.

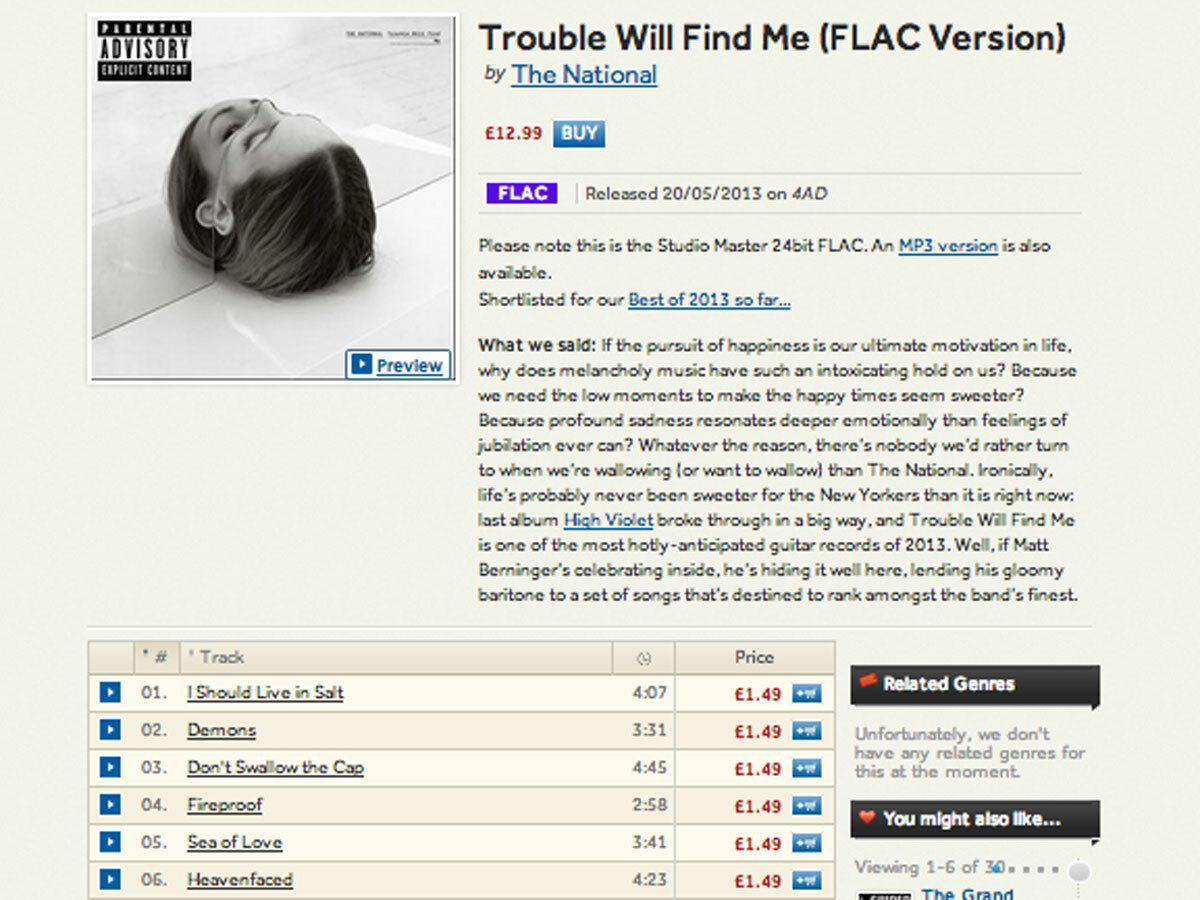

At the moment the choice is fairly uninspiring unless you want those aforementioned jazz, classical and old records. Manufacturer-run sites like Linn Records, Naim Label and Bowers & Wilkins Society of Sound feature a small selection of 24-bit material, while 7digital has albums by The National and Radiohead but little else. Neil Young’s Pono store looks likely to be made up mostly of re-releases.

This needs to change, and change soon, if hi-res is to even approach the mainstream. While there’s nothing wrong with releasing old re-mastered material, the labels need to offer new stuff too. Linn Records, for instance, has Katy Perry’s latest album available in 24-bit/44kHz quality alongside more traditional stuff like Mike Oldfield and Bach – but really the labels need to start releasing 24-bit versions of every album as a matter of course.

That Katy Perry 24-bit album costs £18 though – is the quality that much better than MP3 or CD?

While it certainly sounds better than compressed MP3, there exists some controversy over whether 24-bit music offers any discernible jump in quality over 16-bit/44.1kHz CD quality. CD, the argument goes, was mathematically designed to offer the best audio quality, covering the full range of frequencies that the human ear can perceive, and therefore it’s a scientific fact that 24-bit is a case of the emperor’s new tunes – or, as a scathing piece by audio codec expert Monty Montgomery at Xiph.org puts it, “a solution to a problem that doesn’t exist, a business model based on willful ignorance and scamming people.”

We’ve listened to 24-bit SACD and DVD-Audio albums that sounded markedly better than the 16-bit CD versions – so were we just imagining it? It seems likely that the re-mastering of those albums is a key factor: albums mastered for Hi-Res Audio tend to retain a greater dynamic range – the range from the quietest parts to the loudest parts of the recording – and that will sound better on decent hi-fi equipment or headphones.

Modern CDs tend to be ‘louder’ with a more tightly compressed dynamic range: mastered to sound ‘better’ on the radio and cheaper equipment (Metallica’s Death Magnetic LP came under fire for its highly compressed sound – in fact a song from the album featured in a Guitar Hero game was far better-sounding than the CD version, due to coming direct from the master tapes and retaining a greater dynamic range). A push towards Hi-Res Audio and so-called “Studio Master” quality will hopefully mean a push for albums mastered twice: once for hi-res and once for ‘normal’ CD. And that can only be a good thing for music lovers.

But will it go massive? The record companies and manufacturers have their work cut out, in our opinion: MP3 downloads and Spotify streaming is incredibly convenient and cheap compared to Hi-Res Audio’s giant file sizes and higher pricing – and we’ve seen time and time again in the tech world that convenience wins out. And it’s also worth nothing that big players like Apple and Sonos don’t seem interested – neither offers more than 16-bit compatibility on its products. So hi-res is coming – but without a real commitment from the industry it may well remain trapped in an audiophile niche.

Image credit: Anthony Nguyen