Stuff Hall of Fame: Acorn Archimedes, the original ARM computer

This Acorn RISC Machine began a revolution in low power, high performance chip design that gave rise to the smartphone revolution. And boy, was it fun

It was lunchtime at end of the 1980s. Outside the science classroom there was the usual cacophony of dinner money embezzlement, girls perfecting Madonna’s moves and lads giving each other Chinese burns.

But inside the lab there was focused silence. The boys of the computer club tapped a simple program into the school’s brand new Acorn Archimedes 305.

Little did they know they were abusing a technology that would later make the post-industrial, mobile revolution possible.

Eureka!

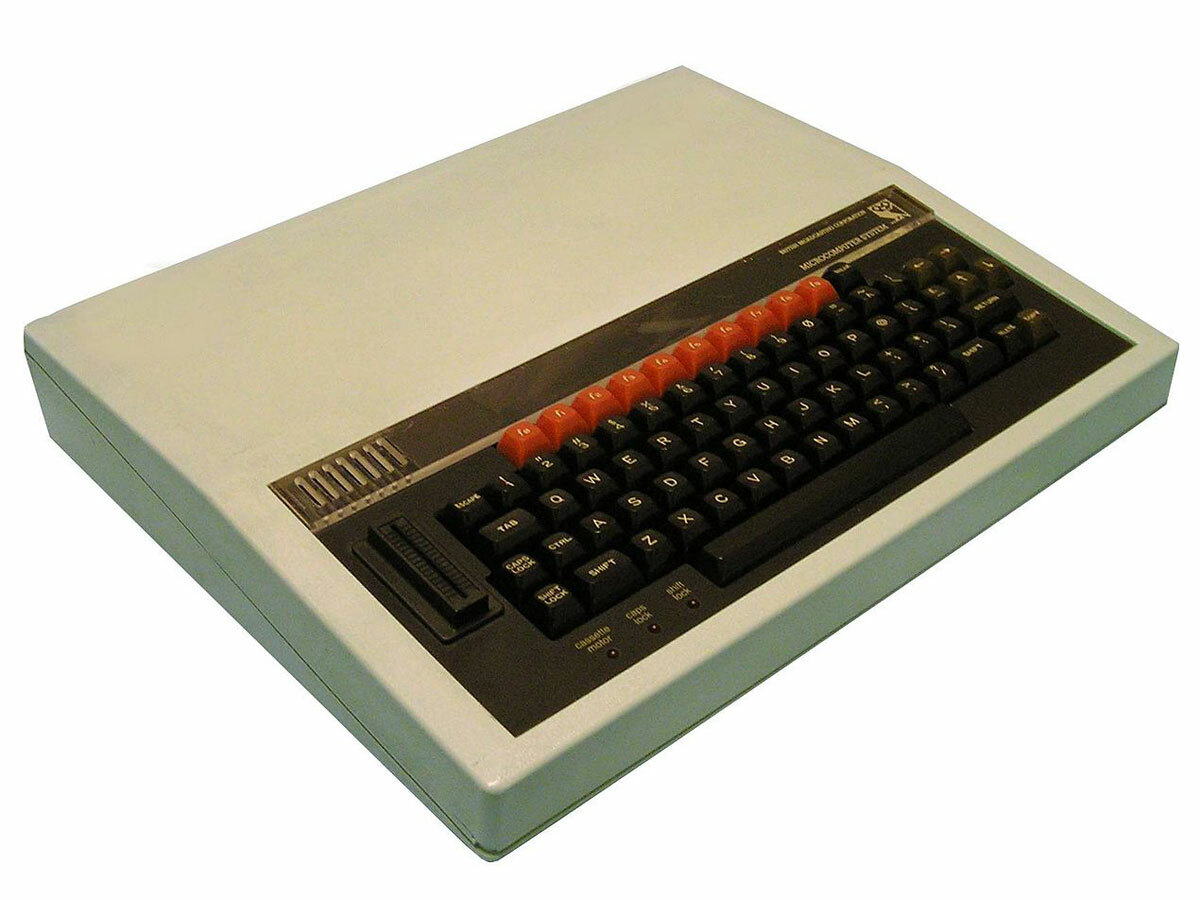

Billeted in Cambridge, Acorn Computers Ltd enjoyed an early marketing coup when they won a contract to produce the BBC Micro, a compact home computer with the backing of the nation’s biggest broadcaster. The 8-bit machines were ubiquitous in schools throughout the ’80s. It went through several iterations, each retaining the distinctive black and red keyboard colour scheme.

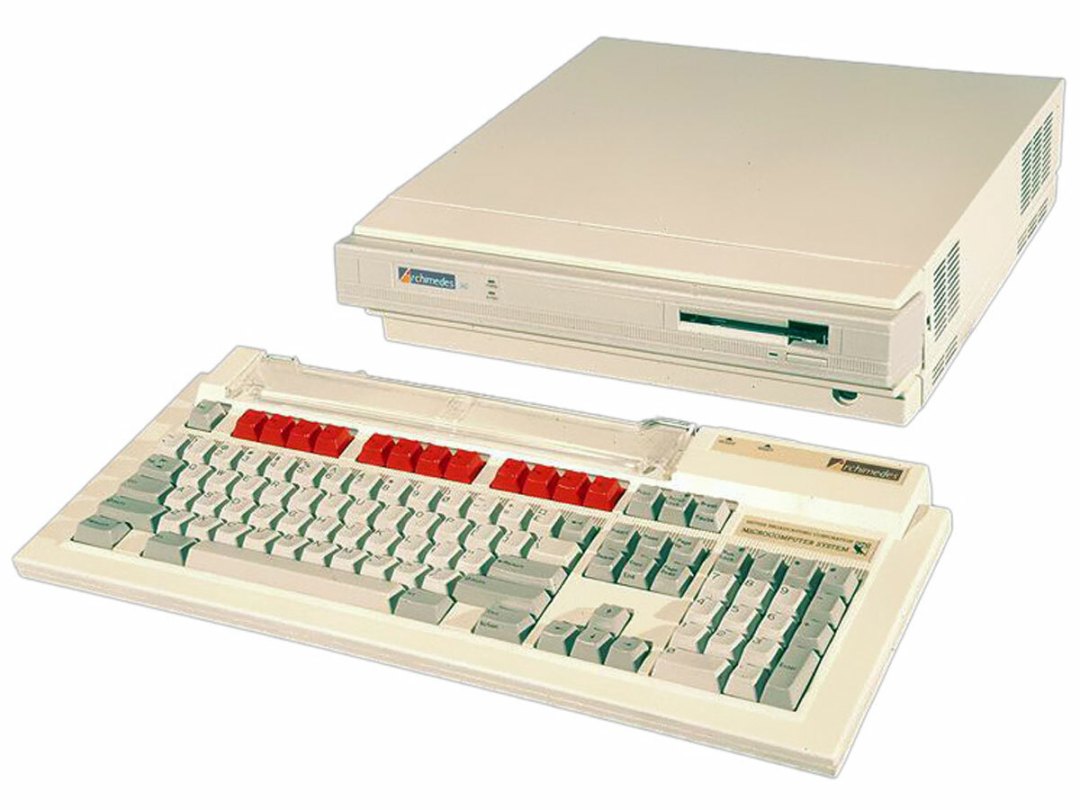

Released in 1987, the Acorn Archimedes built on the success of the BBC Micro and was ahead of its time in two keys ways; it had an operating system with a graphical user interface and, even more importantly, it had a new 32-bit CPU; the ARM2.

Though the Archimedes was the first computer to boast a full ARM-based architecture, the seeds for its development went further back – almost as far as the original BBC Micro – to 1983.

As the story goes, Acorn looked at every other chip in the market for its next generation of machines, including Intel’s 80286 processor and the Motorola 68000 that powered early Macs. None of them met Acorn’s stringent criteria, so they made their own.

Before the Archimedes, Acorn equipped existing machines with prototype ARM1 chips as second processors, simulating the Archimedes instruction set in a program written in BBC BASIC. The in-house machines were used for CAD operations and the intensive process of designing a next generation computer from the floor up.

In true Terminator fashion, the ARM processor was actually used to develop itself…

Wired for Sound and Video

The Archimedes was an impressive machine, the sum of many parts and a leap forward from its innovative predecessor.

“It had a quality sound system integrated into standard hardware – 8-channel stereo when almost everyone else had a beep,”says Kevin Coleman, who was the Head of Group Marketing at Acorn during the Archimedes’s life cycle, “There was a ROM-based operating system, so it was pretty much instant on rather than having to boot from disk.”

Another notable feature at launch was RAM capacity; 4MB for the top of the range Archimedes 440 at a time when 512k to 1MB was standard in home machines. It also came with a hard drive controller, with accompanying HD depending on the model. A separate video chip gave the machine 256 colour capability at lower resolutions (640 x 256), leaving contemporary competitors like the Commodore Amiga in the dust.

Though lauded for the thousands of colours it could display in static HAM (‘Hold and Modify’) mode, the contemporary Amiga 500 could only manage 32 colours in normal operation. ‘Pwned’ is the word… or would be if had existed in the ’80s.

Strong Arm

The Acorn Archimedes was steadily updated from 1987 to 1992, with its most powerful iteration boasting an ARM3 CPU, 8MB of RAM and an internal hard disk with a whopping 160MB capacity. More than comparable in power to the i486 Intel PCs becoming popular as business computers at the time.

Huge users of the original BBC Micro – in part due to the BBC’s Computer Literacy scheme and the simplicity of BBC Basic – British schools were a key market for the Archimedes. But they weren’t weren’t the only customers.

Our early Archimedes memories are filled with graphic fragments of BASIC programming and word processing, multimedia encyclopedias, desktop publishing and spread sheets. It was a jolting change from the green screen world of the early PC.

But when the parents weren’t looking the Archimedes came into its own. It was one of the first serious computers to do serious games, including the best version of space trader and galaxy explorer Elite.

The Archimedes video processor enabled smooth 3D graphics, while 8-channel audio meant that a MIDI version of The Blue Danube had never sounded as good. “It was favoured as a fast games machine for a while. In house we had a networked version of Quake which was pretty impressive,” says Coleman. “The graphics and multimedia were valuable for simulation or testing. Westlands used them for helicopter maintenance training, for example.”

ARM went everywhere

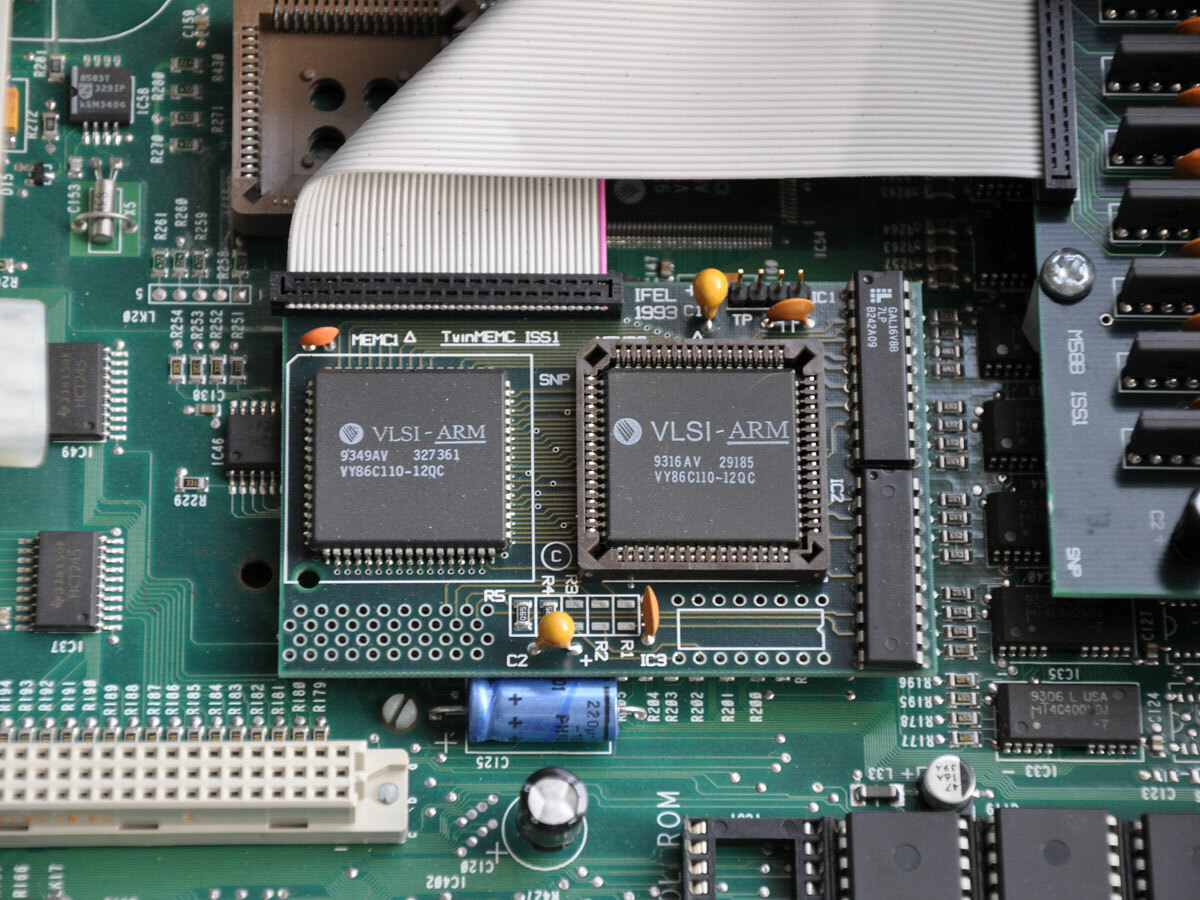

And driving these powerful applications, was the ARM (Acorn RISC Machine) processor; the chip designed to be cheap to manufacture, cheap to run and easy to program. RISC means ‘reduced instruction set’. With fewer instructions, the chip was easier to manufacture and fit onto a smaller, cheaper, wafer of silicon.

Acorn devs did the job so well that 25 years later we’re still using them. Not the exact same chip, of course, but CPUs built with the same philosophy, with the same design attributes and the same name.

“Archimedes gave us the Oracle network computer, the first digital interactive TV set-top box…” says Coleman. “And remember – the Apple Newton.”

Recognising the importance of the chip, the development of ARM was spun off into a separate company, part owned by Apple. These days the acronym stands for Advanced RISC Machine – but it’s still the low consumption, streamlined chip that Acorn devs designed.

…and now ARM rules the world

ARM chips are now in set-top boxes, netbooks, game consoles and tablet PCs. And smart TVs, sat-navs, smartwatches and fridges. And servers, hard disks, chip-and-PIN cards, washing machines, music streamers… even brake pads.

They power most smartphones, including almost all Androids. Raspberry Pi, the closest thing we have to a modern-day BBC Micro, has an ARM at its core. The A-series CPUs powering iPads and iPhones are built around ARM processors. The next ones will be too.

As ARM co-founder John Biggs once quipped to Stuff, “You know how people say you’re never more than 3m away from a rat? You’re probably never more than 3m away from an ARM chip.”

All this is possible because a British company and a team of ten Cambridge engineers were cocky enough to think they could make a chip that was better than the existing American designs, the hot-running, expensive Motorola 6502 architecture that had been dominant since the ’70s.

With BBC Micro designers Sophie Wilson and Steve Furber at the lead, the team took just 18 months to assemble their prototype. A couple of years later, they’d built an entirely new kind of computer around it.

“It was described at the time as ‘typical Acorn arrogance’” says Coleman. “This wouldn’t have happened if Acorn hadn’t wanted ARM for the Archimedes. Makes you think, doesn’t it?”