The next sensor: how your future wearable will know how healthy you are

The next breed of wearables will give us a better idea of what health really means - and it starts with Samsung's Simband

How do you know when you’ve walked 500 miles or if your heart is racing? You look at your wrist, because pop romanticism is just another set of statistics to a smartwatch or fitness band.

But while today’s wearables are great for telling you whether or not you’ve hit your health and fitness goals, the technology on the horizon will give you detailed real-time analysis of your state of wellbeing, calculated to more than two decimal places.

It’s the era of the ‘quantified self’, when everything about you can and will be measured all the time. And it starts with, for example, the Samsung Simband…

Next-gen health tech

The Simband was first announced and shown off last year, but as there’s still no confirmed launch date yet, it may never get beyond prototype in its current form.

That’s not to say there isn’t a lot of interest in it from both consumers and scientists: it is to today’s smartbands and watches as Great Ormond Street Hospital is to a box of plasters. You think your heart-rate monitor is pretty slick? This thing can tell you the quality of your sweat.

The design of the Simband is most likely to change, but at the moment its gently curved body should sit comfortably on most wrists. The whole design and schematic will be released as an open-source template, though, so you could theoretically build your own into pretty much anything.

The main screen is like having a Star Trek medical bay on your wrist. Just put it on and you get graphs measuring your pulse, number of steps, blood pressure, blood oxygen levels and temperature.

Described as a “portable nursing station” for medical research, it’s the last word in quantified self-technology as it stands today – although Samsung even says it will add extra sensors if a customer requires them.

Related › Fitbit Flex review

What lies beneath?

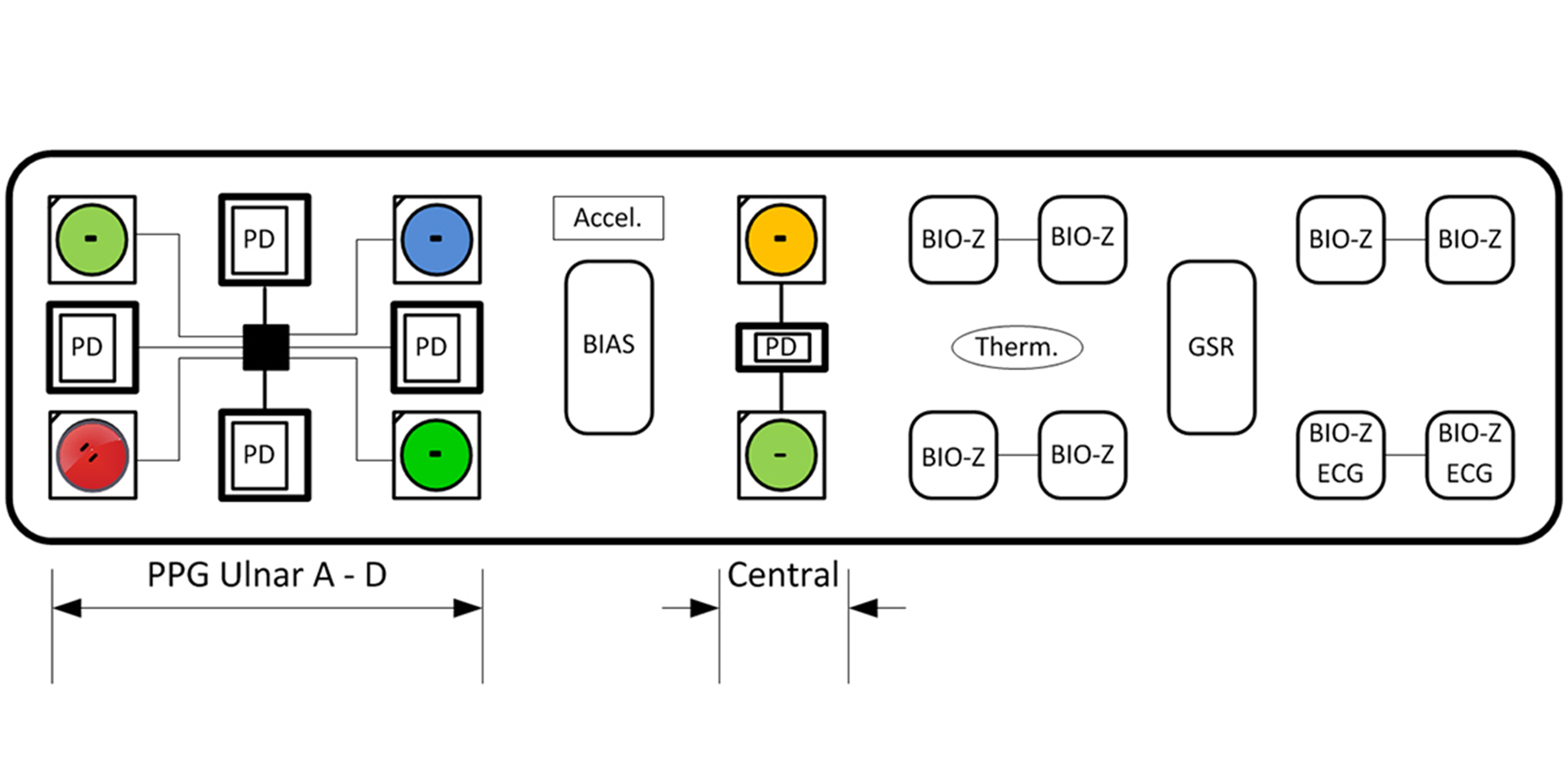

The 24 sensor sites on the bottom of the strap feed into six different types of sensor which relay data back to the Simband and then on to the cloud.

For starters there’s a simple electrocardiogram (ECG) which takes your pulse. Then there’s a bio-impedance sensor (BIO-Z) – or rather several of them – which measure blood flow in an artery. Third is the optical photoplethysmogram (PPG), which measures oxygen levels. The PPG monitor is similar to the clothes peg sensor used in hospitals which clips on the end of your finger.

Another sensor measures galvanic skin response – or how hard you’re sweating – and a thermometer and a standard accelerometer bring up the rear.

Put them all together and these sensors can do clever things such as work out blood pressure, too.

RELATED › Apple Watch review

It’s all about the data

Back in the early days of smartphones, Samsung researchers pioneered ways to work out whether or not you were standing up or lying down based on data from just a couple of accelerometers in the Galaxy S2. With all the data captured from the Simband, who knows what they’ll be able to predict?

For instance, while increased heart-rate and sweat might be a simple sign of stress, if your smartband also detects low blood-oxygen levels (via measurements from the PPG sensors) then the odds are you have something medically wrong with you. A virus, perhaps, or sepsis or any number of diseases. You’ll still need a medical professional to diagnose it, but it’ll be a warning that you need to get something checked out.

Indeed, the Simband is perhaps best viewed as a tool for doctors and health practitioners to prescribe rather than for the average person to buy for their own use as they would a Fitbit Flex or Apple Watch.

"A lot of that data will be difficult for a lay person to use," explains GP Richard Harkness, "and something like the Simband may have more practicality when used in conjunction with a medical professional."

There are, says doctor Harkness, several obvious applications. "A frail elderly patient under the care of doctors could wear one of these and if parameters go outside preset limits (let’s say her pulse rate rises, temperature increases and sats decline) it could alert them that they have a chest infection starting again.

"Or they could also be worn on wards to allow patients to have more freedom to move around while doctors still keep a track on their health, or even to allow them to go on day leave to their homes."

Plus, as the good Doctor House from TV’s, er, House puts it, patients are somewhat unreliable. It’s not so much that everybody lies, more that when the doctor asks you “have you experienced any shortness of breath?”, your idea of shortness of breath and their idea might be two different things.

A device such as the Simband doesn’t lie, instead giving an accurate report of what’s been going on over a period of time. That’s not just important for diagnosing your wellbeing, it will almost certainly lead to new insights about diseases too.

So while the likes of the Simband might not make you healthier, they should at the very least help doctors make you less ill. And that’s not bad for starters.